KEEPING people informed is a daunting challenge to community journalists as they struggle to stay in circulation, given the community quarantine restrictions and drastically reduced advertising revenues.

The community newspapers are bearing the brunt of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic. Several of them have ceased producing print editions, some have stopped operations, while others have gone online through their websites or social media networks.

There is no doubt that Covid-19 is the biggest story today, not only in the communities or in the Philippines, but across the world, with the number of positive cases and deaths growing by the day. The crisis is still upon us and, after three months on lockdown, it is still difficult to understand the impact of Covid in our lives and in journalism.

At this time, the demand from the audience for trustworthy and credible information has been unprecedented. This time presents a great opportunity for independent media, for the community press, to showcase the importance of good journalism and broader engagement with the community.

At the same time, the local press is besieged with more problems over resources and access to information.

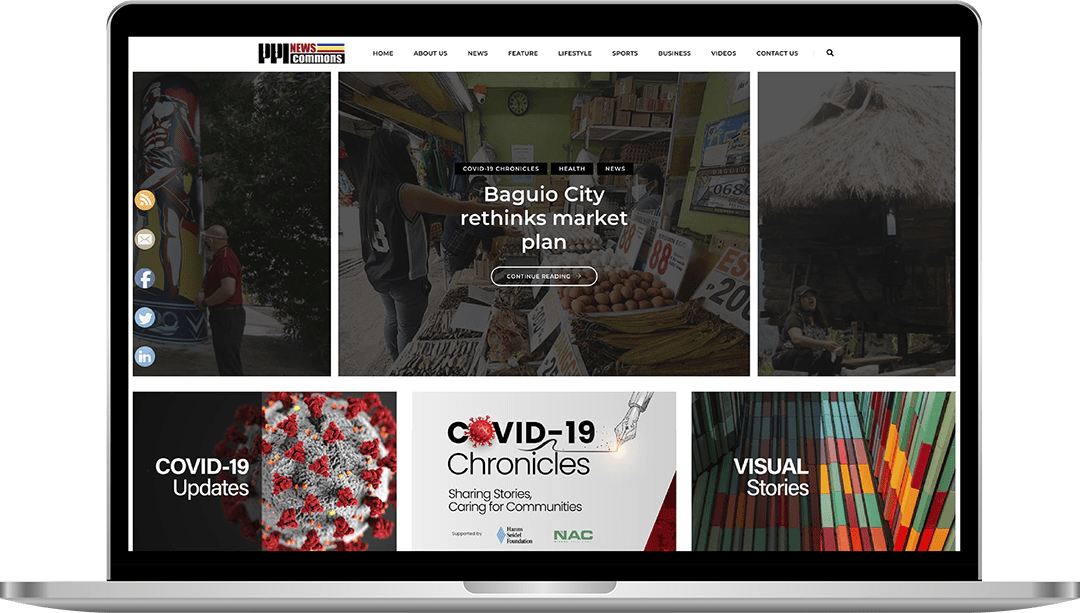

Over the weekend, I had a chance to join a webinar titled “Covid-19 Chronicles: When (Reporting) Duty Calls,” organized by the Philippine Press Institute (PPI) with some of the country’s best community journalists.

Moderated by former Southeast Asia Press Alliance executive director Tess Bacalla, multi-award-winning community journalists Carol Arguillas of MindaNews, Amy Bandiola of Mindanao Times, Alex Pal of Dumaguete MetroPost, Dexter See of Baguio Herald Express and Julius Mariveles of Bacolod City-based Digital News Exchange dissected how the problems had become far worse as a result of the community lockdown during the Covid pandemic in terms of operational, financial and editorial aspects.

The problems or challenges presented were basically the same — limited coverage because of the mobility restrictions, poor access to information and meager resources because advertising revenues have substantially declined.

The panelists also shared how they’ve been grappling with the decline in advertising revenues while trying to continue producing news for their audience.

According to PPI Executive Director Ariel Sebellino, nearly half of member-community newspapers of the organization had been forced to temporarily cease printing operations because of the pandemic. He said the ongoing health crisis had made it more difficult for the community press to perform such duties as news gathering in the field as they risk getting infected by Covid-19.

PPI is a nonprofit private association of at least 60 newspapers and the oldest professional media organization in the country, with a mandate to defend press freedom and promote ethical journalism practice. Its member-newspapers include almost all of the major broadsheets based in Metro Manila as well as provincial and community newspapers in Luzon, the Visayas and Mindanao.

Arguillas said coverage of Covid-19 is quite challenging given the limitations on movement, press conferences are conducted online and the government will not release the details you need unless you press them unrelentingly.

One of the good things the Covid-19 pandemic has brought is, as PPI Chairman and President Rolando Estabillo said in his opening remarks, that the media in general, not only the community newspapers, were forced to embrace technology and learn how to use the digital tools to be able to keep doing their job.

The Manila Standard, of which Estabillo is chief executive officer and publisher, stopped coming out with a print edition for a while and just kept its presence online.

According to See, 80 to 90 percent of the PPI member-publications in Northern Luzon had ceased printing, but hoped to resume soon.

Among the community newspapers that have stopped printing are SunStar Baguio, The Northern Forum in Tuguegarao, Palawan News and the Pahayagang Balikas in Batangas.

We don’t know when this crisis will end. The question is, until when can we survive this? Because it is unlikely that we could go back to the pre-Covid normal, many have found creative ways to keep going, such as DNX, which is offering heavily discounted advertising packages to small businesses. Bacalla noted that this exemplifies a sense of community, of healing as one. You help them promote their business and, at the same time, they help you with advertising fees.

Another creative approach in turning the challenges into opportunities is what Cabusao termed as co-branding or working with schools to offer a program such as “newspaper in education” program, or using the newspaper as part of the curriculum. This would not only help increase subscriptions , but also make the students aware of what’s happening around them and help them develop media or information literacy.

Perhaps, it would also help to find other means to spread information such as shifting to a new medium like podcasting or further increasing presence on social media networks that could also help establish the credibility of a news organization.

Exploring cashless transactions such as subscription payments through PayMaya, PayPal, or G-Cash is also a good way to promote the paper. Bacalla said the community press had to review their business models and adapt to the situation and the consumer demand.

Mariveles highlighted the problem of access to information in view of the mobility restrictions and lack of transparency in government offices. Perhaps we also have to consider that government offices are operating on a skeleton force set-up and may not have enough people to cope with work demands. But then, that should not be an excuse for inefficiency.

Bigger challenges lie ahead, particularly in monitoring government spending of the billions of pesos allotted to Covid response. There was a report a few days ago that donations alone had reached P6.5 billion for the government’s Covid response. Where did these monies go? And the billions of pesos and other budgets for government dole-outs? Did these really go to the poorest of the poor, or did they end up in the pockets of some politicians?

How about the supply contracts? We all know that during emergency situations such as what we have now, public bidding is not required, so we should demand more transparency.The problem with disinformation also exists, and perhaps it has grown bigger. While we are expected to churn out accurate information, the problem gets worse when official sources present inconsistent or incoherent data, information or policies.

But in the community, we should not shirk from our duty or obligation to pass on as accurate information as we can. The information from the community or grassroots must be correct so that when the national government makes decisions and policies, these are based on correct information.

The role that the community plays during crisis situations such as we have now cannot be overemphasized. The question that hounds us is, how much longer can we survive this situation?