JASCOR Gets a Quill

By Tess Bacalla

Stories that made the cut in the 2014 and 2015 Journalism Awards for Sustainable Construction, otherwise known as JASCOR, were collectively recognized at the recently concluded 2017 Philippine Quill Awards for Communications Skills — Publication Category.

Holcim Philippines, the building solutions company that funds JASCOR and a member of LafargeHolcim Holcim Group, a global leader in the construction materials industry, received the Philippine Quill award from the local division of the International Association of Business Communicators during the 15th Philippine Quill Awards held at the Marriott Hotel in Manila.

The Philippine Quill is considered the most prestigious award in business communication in the country.

JASCOR is a joint undertaking of Holcim Philippines and the Philippine Press Institute, the country’s biggest national association of newspapers. It aims to recognize stories from the print media that help generate increased public awareness of the concept of sustainable construction and relevant issues.

One of JASCOR’s winning stories — which bagged the annual competition’s 2015 grand prize in the national newspaper category — is an inspiring piece, “Strong, cheap homes for ‘Yolanda’ victims,” penned by Philippine Daily Inquirer correspondent Mozart Pastrano, that gave the nod to the “wisdom of vernacular architecture”.

Take that to mean — in the case of some of the survivors of typhoon Yolanda (international code name: Haiyan), which packed winds exceeding 300 kph and toppled just about every structure in its path — new and sturdier homes that leveraged indigenous innovations, making “passive cooling, natural lighting and ventilation” possible. The structures, built where old and typhoon-shattered ones used to stand, were designed to withstand winds up to 250 kph and are a “pioneering community-driven approach to recovery and rehabilitation.”

Nanay Marina, the proud owner of one of these structures, beamed with pride on seeing her newly minted house for the first time, a collective achievement of a community of survivors who put their hands together to build their homes, assisted by UN Habitat.

Gone are the scraps that made up what had been her home for close to two decades until it was levelled to the ground by the 2014 super typhoon. “Now we can go on with our lives,” said the then 69-year-old resident of Barangay Baybay, Roxas City, in the Capiz Province, one of the areas ravaged by the typhoon.

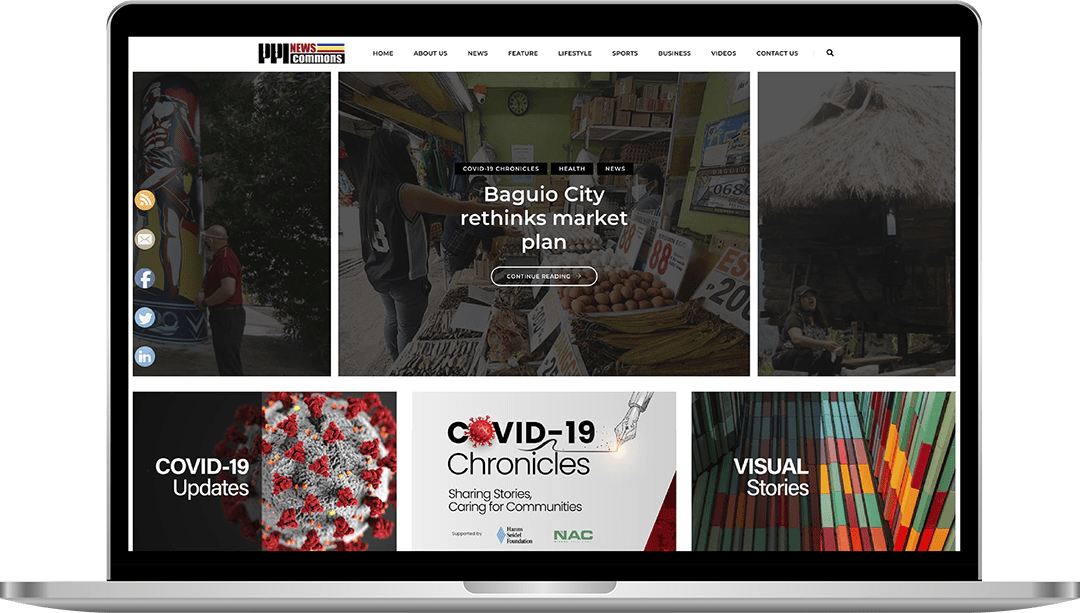

In her winning story, Business Mirror correspondent Marilou Guieb, sharing top honors in the national newspaper category with Pastrano — described, in great detail, one of the remaining “pockets of green and spiritual spaces” in the City of Pines, now hobbled by a slow but steady shift from the once chilly air to “concrete island heat (and) pine-clad open spaces to traffic snarls.”

In her piece, titled “The Maryknoll nuns’ Earth House provides calm in a city of chaos,” the Baguio City-based journalist talked about an ecological sanctuary that is at the heart of the Cosmic Journey, a guided tour organized by the religious order, comprising 14 stations that “go back in time, featuring “pathways strewn with flowers and ferns and shaded by towering pine trees.”

The ecological stroll winds down at the Earth House, an interesting and innovative “mix of old architectural wisdom and modern construction,” showcasing sustainable construction.

The builder, neither an architect nor an engineer, and admittedly “totally naïve about construction,” was given free hand by the directress of the Maryknoll Ecological Sanctuary,

Emma Villanueva, who lived near the Maryknoll compound and whose kitchen cafe that she personally designed impressed the Maryknoll nuns, embarked on her own creative journey when she was tapped by the latter to build and design the Earth House.

Among others, she experimented with clay soil, sand, and straw until she came up with the right formula for creating bricks that remained intact even when dropped to the ground. The resulting mud bricks reinforced the bamboo slats that formed the walls. Shards of used wine bottles and discarded jars — featuring an array of colors — were tucked into the bamboo weaves, letting natural light in while enhancing the aesthetic look of the entire structure.

Broken Italian tiles that sold for P40 per box, and which were cut to the desired sizes and shapes, formed the sink while natural dyes in their organic hues that gave the house an even more impressive look were extracted from plants — knowledge of which came in handy, thanks to village women familiar with these plants. Other notable features of the earthen house were cogon roofing fitted with sprinklers, and solar panels given freely by a local distributor, one of many who donated time and effort to building the house.

“If she can do it with just mud, sand and water, so can communities, and governments—and no one needs to be ever homeless,” concluded Guieb.